|

Related Pages: |

Thursday, February 8, 2001

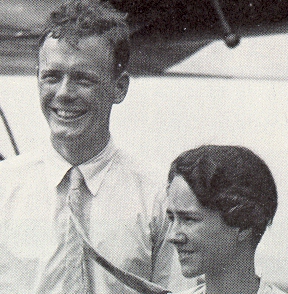

Anne Morrow Lindbergh, the wife of aviator Charles A. Lindbergh, who became his co-pilot and wrote extensively about their pioneering adventures in flight, died in her sleep Feb. 7 at her rural Vermont home. She was 94.

Mrs. Lindbergh, who published 13 books of memoirs, fiction, poems and essays, was a shy woman who was thrown into the spotlight of her famous husband immediately after they met in 1927, shortly after he made his famous solo flight across the Atlantic.

She soon became her husband's co-pilot, co-navigator and radio operator. The couple's flights across oceans and around the world fascinated the American public.

In 1932, the already-famous Lindberghs drew worldwide attention when their first child, 20-month-old Charles Jr., was kidnapped and killed.

In an introduction to her journals, she recalled her famous fiance as "a knight in shining armor, with myself as his devoted page."

Charles Lindbergh and Anne Morrow were married May 27, 1929, and later had six children. Charles Lindbergh died in 1974.

From 1929 to 1935, the Lindberghs flew across the United States on tours promoting air travel as a safe and convenient method of transportation. In 1930, she became the first American woman to get a glider pilot's license.

On their flights, while her husband sat in the front seat, Mrs. Lindbergh was in the rear seat, operating the radio and gathering weather conditions and landing information.

On April 20, 1930, the Lindberghs set a transcontinental speed record, flying from Los Angeles to New York in 14 hours and 45 minutes. Mrs. Lindbergh was seven months pregnant at the time.

In 1934, Mrs. Lindbergh was the first woman to win the National Geographic Society's Hubbard Gold Medal for distinction in exploration, research and discovery.

Many of her books were autobiographical, including five volumes of diaries and letters that gave detailed accounts of the Lindberghs' lives from the 1920s through the 1940s.

In an introduction to "Hour of Gold, Hour of Lead," the volume covering the years from 1929 to 1932, she wrote of the joy flying gave her: "Flying was a very tangible freedom. In those days, it was beauty, adventure, discovery -- the epitome of breaking into new worlds."

In the same book, she wrote of the pain she and her husband felt after the body of their son was discovered in May 1932, 10 weeks after the sleeping baby was kidnapped from their house near Princeton, N.J.

"We sleep badly and wake up and talk. I dreamed right along as I was thinking -- all of one piece, no relief. I was walking down a suburban street seeing other people's children and I stopped to see one in a carriage and I thought it was a sweet child, but I was looking for my child in his face. And I realized, in the dream, that I would do that forever."

Mrs. Lindbergh, who struggled to maintain her family's privacy, wrote of her disdain for the media spotlight: "I was quite unprepared for this cops-and-robbers pursuit. . . . I felt like an escaped convict. This was not freedom."

She wrote in her diary that when her husband landed in Paris, he was "completely unaware of the world interest -- the wild crowds below. The rush of the crowds to the plane is symbolic of life rushing at him -- a new life -- new responsibilities -- he was completely unaware of and unprepared for."

She broke with her tradition of privacy when she opened her late husband's and her own papers to biographer A. Scott Berg, whose book "Lindbergh" came out in 1998. In 1999, another book came out, focusing this time on Mrs. Lindbergh: Susan Hertog's "Anne Morrow Lindbergh: A Life."

Privacy Policy | Terms and Conditions | This site is not affiliated with the Lindbergh family,

Lindbergh Foundation, or any other organization or group.

This site owned and operated by the Spirit of St. Louis 2 Project.

Email: webmaster@charleslindbergh.com

® Copyright 2014 CharlesLindbergh.com®, All rights reserved.

Help support this site, order your www.Amazon.com materials through this link.