|

Related Pages: |

|

HH-3E, tail number 66-13289 (Jolly 36 or AF Rescue 289) lifted off Clark AB, Republic of the Philippines at 0320 Hrs. on Easter Sunday morning, 1972. The mission was to fly over 600 miles south to Southern Mindanao, and attempt to recover General Charles A. Lindbergh from the Tasaday mountain range.

Gen. Lindbergh had been airlifted into the position, along with an American news team, to document and add credence to a research being conducted of a group of 25 natives found living in 3 caves. They had been dubbed the “Tasadays”, since they were discovered in the Tasaday range. It was at first believed that they were original “stone age people”.

The research team had been airlifted into the area via a French Allouette helicopter being flown by a retired Filipino AF helicopter pilot. Previously three Filipinos had trekked into the area and built a platform in the top of an 80 foot tree, over which the helicopter hovered and the personnel then jumped from the helicopter to the 10 x 10 pad, and climbed down the tree. The team had set up a camp approximately 100 yards beneath the three caves in which the Tasadays were living.

The research team had been in the area for about three weeks, being supplied by the helicopter, when Gen. Lindbergh and the news team were inserted. They, too, were taken to the pad in the 80 foot tree. Two days after they arrived, the helicopter developed a bad blade and could not be flown. At that point, the U.S. Ambassador to the Philippines, Mr. James Byroade, was notified. He called the 31st Aerospace Rescue & Recovery Squadron, at Clark AB, on Saturday before Easter, requesting assistance in recovering Gen. Lindbergh and the research team.

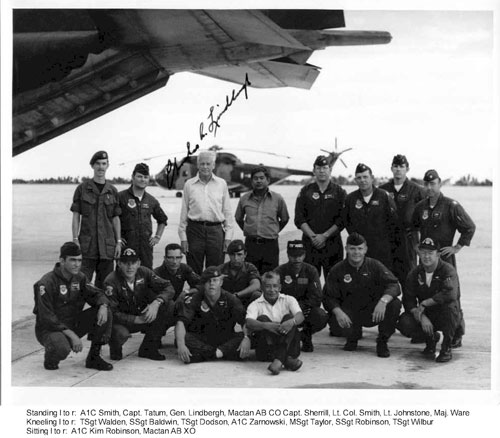

The Commander, Lt. Col. “Bud” Green, called the HH-3E crew, Aircraft Commander - Major Bruce Ware; Copilot - Lt. Col. “Dick” Smith; Flight Engineer - SSgt Bob Baldwin; and Pararescueman - A1C Kim Robinson. The existing situation would require the recovery to be made from an elevation of approximately 3,000 feet MSL elevation, with temperatures which could rise to 35 degrees, centigrade, during the day. The plan was to takeoff as early as possible, so as to arrive in the area prior to the heat of the day. Therefore, a weather check was to be made at 0100 Hrs, with takeoff as soon as possible thereafter, depending on the weather, to fly the 600 miles to the recovery area. An HC-130N, was to take off an hour later to provide aerial refueling and navigation assistance to the HH-3E. The HC-130 crew consisted of Aircraft Commander - Capt. “Kent” Tatum; Co-pilot - Lt. “Rick” Johnstone; Navigator - Capt. Mark Sherrill; Radio Operator - MSgt Taylor; Flight Engineers - TSgt Walden & TSgt Wilbur; Loadmasters - TSgt Dodson & SSgt Robinson; and Pararescuemen - A1C Zarnowski & A1C Smith.

All went well for the helicopter crew for the first 30 minutes or so, when one of the fuel quantity gauges failed. A call was made back to the squadron, and a replacement gauge was loaded onto the HC-130, prior to its takeoff. The exchange of the fuel gauge with the helicopter took place at a small airport on the northern coast of Mindanao.

The HH-3E arrived at the Allah Valley airport, in the valley close to the recovery area, at approximately 1000 Hrs. The entire supply of survival gear and parachutes were off loaded, so as to reduce the helicopter’s weight to the minimum. The Filipino helicopter pilot was taken aboard, to assist in locating the recovery area.

Immediately upon departure, the research team was contacted via HF radio and queried as to whether or not there was a helipad upon which the HH-3E could land. The researchers became so excited they started speaking “Tagalog”, the native Filipino language. We had the Filipino put on the copilot’s helmet to ask about the helipad. “Yes” there was one - 20 meters long and 3 meters wide, hardly big enough on which to land the big HH-3E.

The group had earlier begun to prepare the helipad for the Allouette helicopter, by locating a level area on a “finger ridge”. They removed the trees on the level portion of the ridge, but left one foot high stumps, then took the tops off the trees on both sides of the ridge, thereby forming a large “notch” in the tree line on the top of the ridge. The elevation was approximately 2800 feet MSL, and the temperature was up to 26 degrees C.

Upon locating the “helipad”, I flew several “site evaluation” passes by passing along the main ridge, then turning down the finger ridge to commence an approach to a spot adjacent to the cleared area on the ridge line. We elected to “dump” some fuel, so as to again reduce the helicopter’s weight and thus have some “power reserve” should it be required. The HH-3E was brought to an “out of ground effect” hover adjacent to the helipad, then turned 90 degrees and moved forward so the nose gear was on one side of the ridge and the main gear was on the other. The bottom of the 3 step aluminum “door” ladder was then just inches above the ground.

A1C Robinson was put onto the ground to control how many passengers were loaded at one time. The first load consisted of 5 of the female “interpreters”. To takeoff, I lifted the helicopter enough for the nose gear to clear the ridge, then backed out and made a descending takeoff into the valley below. Lt. Col. Smith had located an “open area” about 3 miles away at a lower elevation, and recommended we set the girls down there, then go back after Gen. Lindbergh. The second load from the ridge line included the General, and 3 or four of the news team. Another load was lifted from the ridge line, with five or six passengers.

Since fuel had been dumped at the beginning of the operation, it was becoming a strong concern. Therefore the passengers from the “open area” were retrieved for return to their base camp. Immediately upon departure from the “open area”, the HC-130 was called to get into position to refuel the HH-3E as soon as we reached the main valley. After refueling, the occupants were off-loaded at the base camp, and the helicopter returned to the ridge for the remainder of the research team.

The total recovery required eight trips off the ridge and since the weather was starting to diminish, only three trips were made from the “open area”. In all, 46 personnel were recovered. Though the main base camp was only about 15 minutes flying time from the remote research camp, it was a very hard three day walk.

Gen. Lindbergh and three of the research team were then taken aboard the helicopter for the return flight. The Filipino was returned to the Allah Valley airport, where the survival gear and parachutes were retrieved.

Though the helicopter had been partially refueled twice during the “ridge line operation”, fuel was again low, in fact the “low fuel” light was shining brightly at the crew upon departure from the Allah Valley airport. As the HC-130 pulled into position for refueling, we noted the left fuel hose (normal refueling side) was not recycling normally. The HH-3E was cleared to cross over to the other side and immediately refueled off the “right” refueling hose. Gen. Lindbergh stated that though he had helped develop air refueling, he had never been in a helicopter for the operation, nor had he been in the receiving aircraft.

We landed at Mactan AB, on the Island of Cebu, at 1540 Hrs., 12 hours and 20 minutes after takeoff and 11 hours and 30 minutes of flying. I basically rested in the pilot’s seat for several minutes after landing. Gen. Lindbergh was hesitant to disembark until I had done so. Of course there were several photographers waiting for him to step out of the helicopter, which may have been why he was hesitant. Gen. Lindbergh told me that he was certain he would not have been able to walk the “hard” three day trip back to civilization. At the time he was 70 years old.

Gen. Lindbergh and the other passengers were loaded onto the HC-130 and flown to Manila that afternoon. We stayed overnight in Cebu City, and returned to Clark AB the following day.

The goal of all “Rescue” missions is to “save” lives. For this mission, the crews were given credit for saving the entire research team, in addition to that of Gen. Lindbergh and the news crew - 46 in all.

|

- Maj. Bruce Ware - Distinguished Flying Cross

- Lt. Col. Dick Smith - Air Medal

- Capt. “Kent” Tatum - Air Medal

- Capt. Mark Sherrill - Air Medal

- 1/Lt. “Rick” Johnstone - Air Medal

- MSgt Taylor - Air Medal

- TSgt. Walden - Air Medal

- TSgt. Dodson - Air Medal

- TSgt. Wilbur - Air Medal

- SSgt. Robert Baldwin - Air Medal

- SSgt. Robinson - Air Medal

- A1C Kim Robinson - Air Medal

- A1C Smith - Air Medal

- A1C Zarnowski - Air Medal

This article has been reprinted from: http://www.jollygreen.org/

Privacy Policy | Terms and Conditions | This site is not affiliated with the Lindbergh family,

Lindbergh Foundation, or any other organization or group.

This site owned and operated by the Spirit of St. Louis 2 Project.

Email: webmaster@charleslindbergh.com

® Copyright 2014 CharlesLindbergh.com®, All rights reserved.

Help support this site, order your www.Amazon.com materials through this link.